So: core inflation is usually measured by taking food and energy out of the price index; but there are alternative measures, like trimmed-mean and median inflation, which are getting increasing attention.

First, let me clear up a couple of misconceptions. Core inflation is not used for things like calculating cost-of-living adjustments for Social Security; those use the regular CPI.

And people who say things like “That’s a stupid concept — people have to spend money on food and gas, so they should be in your inflation measures” are missing the point. Core inflation isn’t supposed to measure the cost of living, it’s supposed to measure something else: inflation inertia.

Think about it this way. Some prices in the economy fluctuate all the time in the face of supply and demand; food and fuel are the obvious examples. Many prices, however, don’t fluctuate this way — they’re set by oligopolistic firms, or negotiated in long-term contracts, so they’re only revised at intervals ranging from months to years. Many wages are set the same way.

The key thing about these less flexible prices — the insight that got Ned Phelps his Nobel — is that because they aren’t revised very often, they’re set with future inflation in mind. Suppose that I’m setting my price for the next year, and that I expect the overall level of prices — including things like the average price of competing goods — to rise 10 percent over the course of the year. Then I’m probably going to set my price about 5 percent higher than I would if I were only taking current conditions into account.

And that’s not the whole story: because temporarily fixed prices are only revised at intervals, their resets often involve catchup. Again, suppose that I set my prices once a year, and there’s an overall inflation rate of 10 percent. Then at the time I reset my prices, they’ll probably be about 5 percent lower than they “should” be; add that effect to the anticipation of future inflation, and I’ll probably mark up my price by 10 percent — even if supply and demand are more or less balanced right now.

Now imagine an economy in which everyone is doing this. What this tells us is that inflation tends to be self-perpetuating, unless there’s a big excess of either supply or demand. In particular, once expectations of, say, persistent 10 percent inflation have become “embedded” in the economy, it will take a major period of slack — years of high unemployment — to get that rate down. Case in point: the extremely expensive disinflation of the early 1980s.

Now, the measurement issue: we’d like to keep track of this sort of inflation inertia, both on the upside and on the downside — because just as embedded inflation is hard to get rid of, so is embedded deflation (ask the Japanese). But in the real world, while some (many) goods behave like this, some don’t: their prices rise quickly with supply and demand changes, and don’t display inertia. So we need a measure that extracts the signal from the noise, getting at the inertial part of the story.

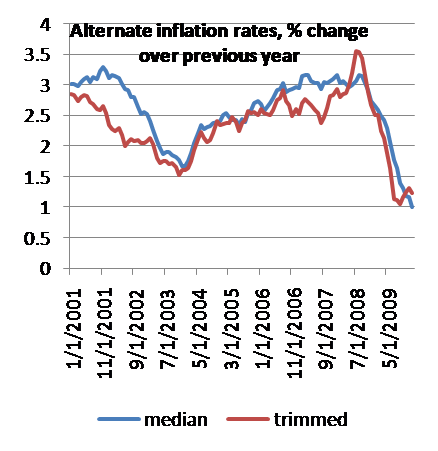

The standard measure tries to do this by excluding the obviously non-inertial prices: food and energy. But are they the whole story? Of course not — and standard core measures have been behaving a bit erratically lately. Hence the growing preference among many economists for measures like medians and trimmed means, which exclude prices that move by a lot in any given month, presumably therefore isolating the prices that move sluggishly, which is what we want.

And what these measures show is an ongoing process of disinflation that could, in not too long, turn into outright deflation:

“Passion and prejudice govern the world; only under the name of reason” --John Wesley

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Core Inflation: why do we need it and how should it be measured?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment